Reiter ... act now on what is possible.

Reiter ... act now on what is possible.

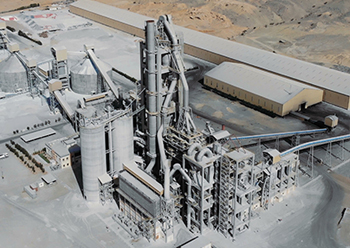

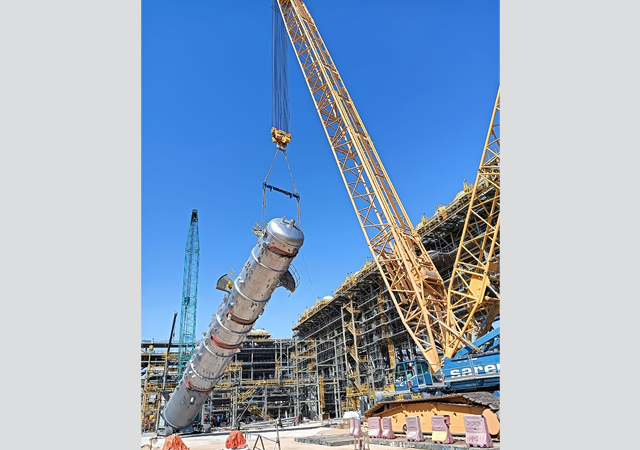

Given that cement accounts for seven per cent of global emissions, decarbonising the cement ecosystem is one of the biggest challenges facing the industry. The Arabian Gulf could take a leading position in decarbonising cement and the broader build environment, given the large number of mega projects and being one of the few regions that is witnessing growing demand for cement, say experts at McKinsey & Company.

They say there are ample opportunities for the cement and concrete sector in the Gulf region to keep in step with global efforts to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

“In the short term by acting on what’s possible now, cement manufacturers can ensure they are prepared to make the required changes necessary to adapt to a decarbonised world,” Sebastian Reiter, partner at McKinsey & Company, tells Gulf Construction’s Bina Goveas.

“This will require the development of techniques that could target both fuel and process emissions at a large scale. This includes levers like energy efficiency, incorporating alternative fuels and options for clinker substitution, including upcoming supplementary cementing materials (SCMs) like calcined clay and recycled concrete waste (also referred as traditional levers in our earlier work1)

“In the mid term, one needs to follow the efforts in Europe and North America to pilot and scale new technologies including carbon capture technologies2.This will be accelerated/supported by the expected growing demand for green cement and building materials,” he states.

|

|

Czigler ... Redesign is propelled by developers. |

Innovations are relevant across the entire value chain. Players along the value chain in the Gulf region should consider three themes in their decarbonisation strategies: redesign, reduce and repurpose, according to McKinsey & Company.

Thomas Czigler, expert at McKinsey & Company, elaborates: “‘Redesign’ is propelled by developers and owners, and the specifications they set, as well as by different regional policies. It entails optimising the design of buildings and infrastructure to reduce the material needed in construction, enhancing the material mix and using new construction methodologies to cut waste and material needs.

“‘Reduce’ includes four ways to minimise emissions of materials beyond cement, this includes using additives, clinker substitutes and alternative binders, changing concrete recipes, optimising production processes, including carbon-cured concrete and recycling building materials – a key lever to circularity.

“’Repurpose’ aims to find ways to make use of the carbon associated with construction, either by capturing and storing it or using it to produce synthetic fuels.”

Carbon capture and storage is only at the beginning of its commercial usage. The technology is still in the scaling phase and storage facilities and the necessary infrastructure for transportation is still in development. Even in the more mature European and North American markets, it is applying primarily by the large incumbents, he admits.

“Hence, the SMEs in the region should start working on the basics, but also follow the development closely. Teaming up with peers might be a good start to pick the right technology. In addition, we see numerous start-ups emerging in the space claiming new and different approaches to decarbonise the process – closely following the development is necessary. Commercial technologies like carbon curing might be already of interest and can lead to meaningful results if a source of CO2 is available close by,” Czigler adds.

There are technologies available – such as energy-efficient selective separation of aggregate and sand – to enable the 100 per cent recycling of concrete by reusing all constituents in the original materials.

“Concrete waste can these days be crushed fine enough to separate the individual components and specifically re-use them. For example, un-hydrated cement fines can be re-used as virgin cement material and hence reduce the CO2 emissions. The key aspect is the deployment of technology and how players in the ecosystem – including end customers such as construction or real estate companies – can support and scale such,” Reiter says.

Construction and demolition waste (CDW) is another aspect where a framework of regulations in the region could directly influence the value of the waste and the potential re-use, the experts point out.

“Pricing of CDW through landfill taxation can drive opportunity costs and, therefore, make recycling of waste materials even more attractive. For example, our calculations show that an increase of landfill tax by €5 ($5.27) per ton of CDW can reduce the CO2 abatement cost of technologies that use CDW as feedstock by up to 60 per cent,” says Czigler.

He adds that given the fact that energy is relatively cheap in the region, the pressure to reduce energy demand in the production process is lower and so is the need to find alternative fuels.

“However, levers like clinker substitution and burning of waste materials instead of fossil fuels are in a lot of regions in the world cost negative and should be explored by the local producers. Improving the own cost position is never of disadvantage,” he points out.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)