Jordan … rights to tender are valuable and can be protected by laws.

Jordan … rights to tender are valuable and can be protected by laws.

What is a right to tender for works? Is it a material right, recognised in law and carrying monetary value? Or is it essentially worthless because it is speculative: nobody can know whether a contractor’s tender will be successful anyway?

We have seen from the development of public sector procurement rules globally, including in the Gulf, that rights to tender (or rights not to be excluded from tendering) are valuable and are capable of being protected by laws. In the private sector, the issue often comes up as part of a commercial settlement: a project developer might press a contractor to accept a lower final account settlement or to withdraw certain claims on the basis that the contractor will be included in the tender list for the next project.

What if that promise is not kept? Is it actionable? And what are the damages arising from that breach? These questions were examined in a recent dispute which reached an English court.

Mallino Development Limited (Mallino) had a very interesting project: to redevelop an old jail into a luxury hotel and visitor attraction. It split the development work into three phases (demolition, excavation and the rest of the works) and engaged Essex Demolition Contractors Limited (Essex).

The contractual set-up was just as interesting: as well as the building contract, the parties entered into a second agreement, to provide that Mallino would retender the second and third phases, and would allow Essex to be involved in that retender. Depending on the outcome of that retender, the original building contract would either be:

• Terminated, with Mallino paying Essex’s demobilisation cost (but not loss of profit and overhead related to the third phase) should Essex be unsuccessful; or

• Novated into the new contract for the second and third phases, should Essex be successful.

In fact, Essex carried out both phases One and Two but Mallino did not retender the third phase. Instead, it entered into exclusive bilateral discussions with another contractor (PIN-CM) and awarded the third phase to it.

Essex brought an action based on its loss of chance to win the Phase Three work, claiming the lost profit and overhead contribution it would have earned. Mallino did not deny its breach but contended that nothing was owed because it could anyway have terminated the building contract. The court rejected that argument, pointing out that Mallino had a positive obligation (in the variation agreement) to include Essex in a retender and, therefore, could not circumvent that by terminating the building contract.

Mallino also argued that Essex would not, in any event, have been awarded the Phase Three works in the retender, for reasons including price, lack of specialist expertise and because (it said) Essex had already damaged the original building.

Looking at the evidence, including a direct comparison between the price from PIN-CM and the price Essex would have been able to give (based on its earlier pricing and taking account of its advantage in being already mobilised on site and its acquired knowledge of it), the court disagreed. On a comparison of specialist expertise, it also sided with Essex. The court decided that Essex had a realistic chance of success in the retender.

Having established the amount that Essex would, most likely, have earned in profit and overhead contribution from a successful bid for Phase Three, the court had to calculate damages based on Essex’s chance of success. Having weighed up that chance, the court awarded two-thirds of the sum Essex would have earned.

This looks like a common-sense decision: the contractual right to be included in the retender was recognised by the court but there was no automatic right to damages for the denial of that right. The contractor had to show a realistic chance of success in that retender and the court’s award was based on its view of that chance.

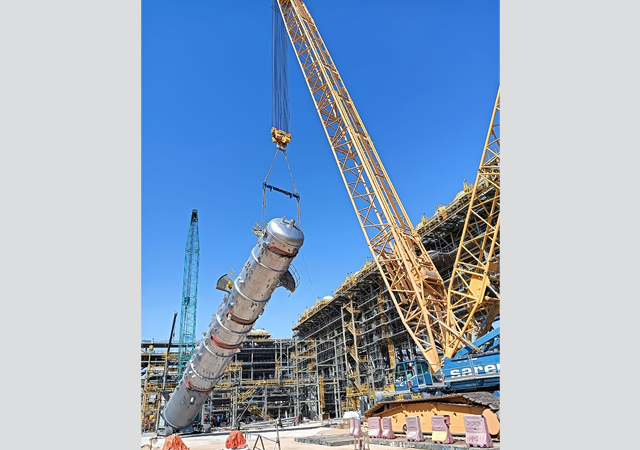

This issue also comes up in large projects which are procured in stages: a contractor might be engaged to carry out a FEED (front-end engineering and design) and to do procurement studies to identify various potential trades and equipment suppliers based on price, suitability and availability. The willingness of the contractor to do this work, maybe for a discounted price, is often influenced by the contractor’s prospects of being engaged as EPC (or other) contractor to build the facility. It is important to avoid overselling or being ambiguous about those prospects. So, whether the FEED contractor will be:

• The selected EPC contractor, subject to the outcome of pricing exercises or other outcomes;

• Included in a competitive construction phase tender with others; or

• Included in the tender, only at the developer’s sole discretion.

parties should make sure that the FEED contractor’s rights are clear in the FEED contract.

Of course, there are often commercial incentives for developers to dangle the prospect of further work in order to get a piece of work done on better terms than if that work were offered on its own. We have seen here the limits to this approach.

* Stuart Jordan is a partner in the Global Projects group of Baker Botts, a leading international law firm. Jordan’s practice focuses on the oil, gas, power, transport, petrochemical, nuclear and construction industries. He has extensive experience in the Middle East, Russia and the UK.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)