Solar power ... bright hope.

Solar power ... bright hope.

Although the oil-rich Middle East has got enough reserves to possibly power its ambitious plans of development at a scorching pace at least for the next couple of decades, it would be wise for the countries in the region to go solar, writes Dr Eckart Woertz*.

Proposals to introduce renewable energy such as solar and wind power in the GCC states might appear as logical as carrying coals to Newcastle, considering that the region stands atop a sea of oil.

However, there are several reasons why solar power should be used to complement the energy mix of the GCC countries. For a start it would spare more oil and gas for exports and feedstock for the local petrochemical industry, while helping the GCC comply with international environmental standards like the Kyoto Protocol and making the region a leader in a technology that is new and relatively labour-intensive.

GCC countries currently have the highest growth rate in oil consumption worldwide (4.5 per cent versus 2.5 per cent for Asia and 1 per cent for the US) and already use 17 per cent of the oil they produce. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects a rise in worldwide oil demand from 80 million barrels per day (mbpd) today to 120 mbpd in 2030. Hopes to meet this projected demand rest on the Gulf countries, as production in other regions is declining (notably in the US and the North Sea). Although the IEA believes that this will be possible once huge investments are made, Saudi Arabia has already sounded a note of caution, while authors associated with the ‘peak oil’ debate (Matthew Simmons**, for example) have questioned whether the Gulf countries are capable of production increases at all. The recent debate in Kuwait about overstated oil reserve figures also hints at this.

In any case, the importance of energy exports from the Gulf will increase dramatically over the years to come, and the less oil and gas the GCC countries use for their own consumption, the more they can stretch the lifetime of their most precious export good. This would also leave more oil as feedstock for their petrochemical industry, which is a crucial part of their diversification strategy. Tourism, another important part of the GCC diversification drive, is also heavily dependent on the availability of fuel: rising oil prices and delays in developing alternative fuels like hydrogen and methanol will lead to prohibitively expensive flights and declines in tourist numbers.

Renewable energy can hardly be regarded as an uneconomical hobby of esoteric tree-huggers anymore. Governments and corporations around the world are acknowledging its importance in increasing numbers, as it offers the long-term vision of clean and limitless energy alternatives for an after oil age. BP has reinterpreted its acronym as ‘Beyond Petroleum’ for a reason, while Chevron has declared that the era of cheap oil is over – it has created a special website to spur discussions about possible solutions (www.willyoujoinus.com). Meanwhile, the 2006 Detroit Auto Show has shown the great interest of the car industry in alternative hydrogen fuel, and many governments, including those of Germany, the US, Japan, India, and China, have created programmes to encourage the development and distribution of renewable energy technology. Wind power plants are already competitive with newly-built coal plants, and contribute 20 per cent and 4 per cent of electricity supplies in Denmark and Germany respectively.

The University of Stanford recently identified suitable regions for wind power generation in a special world atlas. It has argued that the energy needs of the whole planet could theoretically be met several times over by using all the sites identified in the atlas.

The Gulf countries do not have a lot of wind, but everybody who had to walk around the block on a hot summer day in Dubai knows that there is solar energy out there, and loads of it. In fact, the sun supplies 15,000 times more energy than is currently used worldwide. Thus, rather than seeing a problem, one should focus on the challenge of concentrating, collecting, and storing this energy, but unfortunately, the GCC countries’ interest has been limited so far.

In the UAE, the Lootah Group has made a start last year by organising a conference on alternative energies and the Emirates Hydrogen Society is establishing itself as an important network of clean energy players in the UAE.

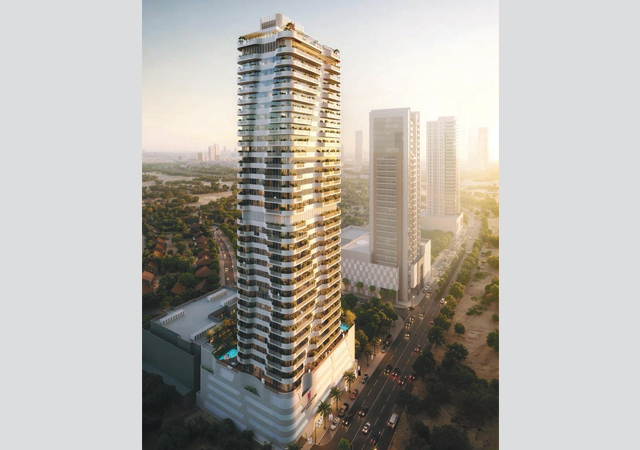

Some insular examples for the usage of renewable energy are already discernible: Solar powered parking meters were the only electrical devices that kept working during Dubai’s power blackout last year and Dubai has also witnessed the building of the first apartment complex in the Middle East to use solar power for air conditioning during the daytime, something which cuts utility bills by at least a third.

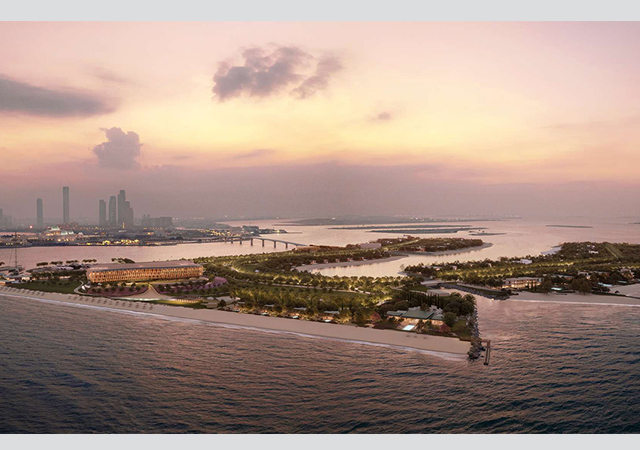

The Bustan Rotana Hotel also made positive experiences by installing solar thermal devices for hot water generation on its roof, while German consultancy company GTZ implemented a wind power plant on Bani Yas Island.

Finally, probably the most important initiative for renewable energies in the Gulf comes from Abu Dhabi: The Masdar project of Mubadala wants to establish a centre of excellence in the field of alternative energies. It will comprise a research institute, a special economic zone, an innovation centre and a clean development company to pursue commercial opportunities in carbon monetisation. It aims to attract technology leaders in the field, provide venture capital for projects and thus wants to transform Abu Dhabi from a mere technology importer to a technology exporter. Ultimately it is hoped that the project will prepare Abu Dhabi for the post-fossil fuel era and will help to maintain its share in the world energy market over the coming decades.

Hopefully projects such as Masdar will lead to large-scale efforts to develop solar power as an important component of the GCC energy mix. Concentrated solar power (CSP) plants, which harvest solar energy with huge mirrors, can heat a liquid and thus fire an otherwise conventional power plant providing electricity to whole towns. They also could power the very energy-intensive desalination plants and produce hydrogen for cars and fuel cells.

In California, CSP plants already provide electricity for over 350,000 people. Photovoltaic devices on buildings produce electricity directly from the sunlight. Combined with storage facilities (like new generation batteries and pressurised air) for times when there is no sunlight, they could decentralise energy supplies and reduce dependency on grids. This would need to be spurred by government incentives along

the line of Germany’s 100,000 Roofs Programme.

Most importantly however, solar power technologies are young, much younger than the Internet or computers, which also needed initial government support to become viable large-scale applications.

Solar power offers low barriers of entry, ample space for technological improvements and enhanced economies of scale. It is relatively labour-intensive as well, in terms of the installation and maintenance of devices and would be an ideal way to spur economic development in the GCC countries by providing more jobs within the region.

It would help the GGC venture into a field of technology where it has no presence whatsoever so far, something demonstrated by the fact that the technology accounts for 16 per cent of emerging stock markets’ capitalisation, but 0 per cent of those of the region.

The GCC would therefore gain an advantage in a technology that will almost certainly play a decisive role in this century as the only viable long-term alternative energy source for today's hydrocarbon-based economies.

*Dr Eckart Woertz is programme manager Economics at the Gulf Research Centre (GRC) in Dubai, UAE.

** Mathew Simmons is a Houston-based investment banker and author of a new book on oil reserves.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)