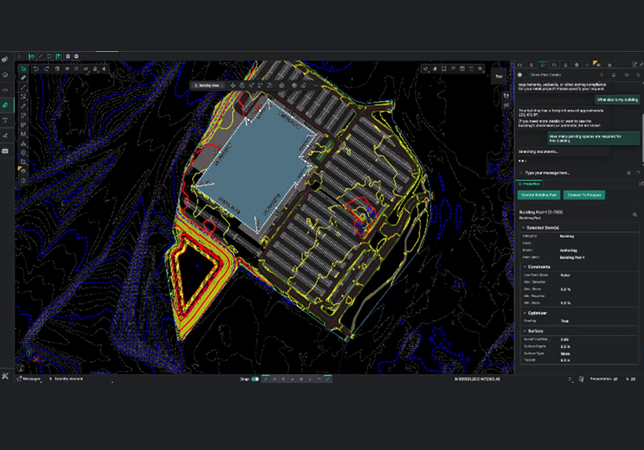

Warner Stand at Lord’s Cricket Ground in St John’s Wood, London.

Warner Stand at Lord’s Cricket Ground in St John’s Wood, London.

The wide choice of American hardwood species available provides architects and designers with a wonderful palette of colours, textures and grains from which to make furniture and design interiors. Yet, what is not available is a very durable wood species that can be considered for outdoor applications such as cladding or decking. Also, their use in structural applications has been somewhat limited by a lack of know-how. However, this is now changing through the application of new, and relatively simple, technology coupled with a readiness to explore timber as a material for a wider range of construction solutions.

The growing outdoor cladding and decking market uses significant volumes of timber, which at present uses very little American hardwoods and, therefore, it provides major scope for growth. In the hardwood forests of the US, there are a few naturally-occurring very durable species, such as black locust, but they are not available in commercial quantities. American white oak has been used successfully in Europe on some large projects, but allowance has to be made for sapwood and preservative treatment may be necessary. However, the application of 10,000 sq m of white oak exterior cladding on the EU Veterinary Centre in the harsh climate of Ireland back in 2002, shows that this species can be used for this purpose if handled and installed correctly.

.jpg) |

|

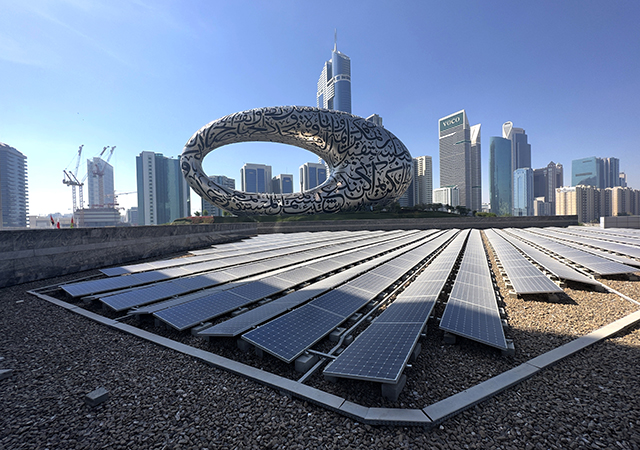

The Cocoon, a collaborative installation by T.ZED Architects and AHEC ... now serving as an observation deck at the Dubai Creek Harbour Promenade. |

Thermal modification

With an aim to develop new markets for American hardwoods, the American Hardwood Export Council (AHEC) – the leading international trade association for the American hardwood industry – realised early on that wood modification was going to play a very significant role. Applying wood modification processes enables a non-durable species to be used externally. Thermal modification of timber is one such generic process and it is adaptable to a range of different timber species.

The modern commercial method of thermal modification was developed in Scandinavia some 30 years ago, enabling the plentiful local softwood resource to be made durable without the application of chemicals. It soon became apparent that certain temperate American hardwood species could also lend themselves very well to the thermal modification process. The leading species are ash, tulipwood, soft maple, yellow birch and red oak. Some lesser-known species such as hackberry, sapgum and basswood also modify very well.

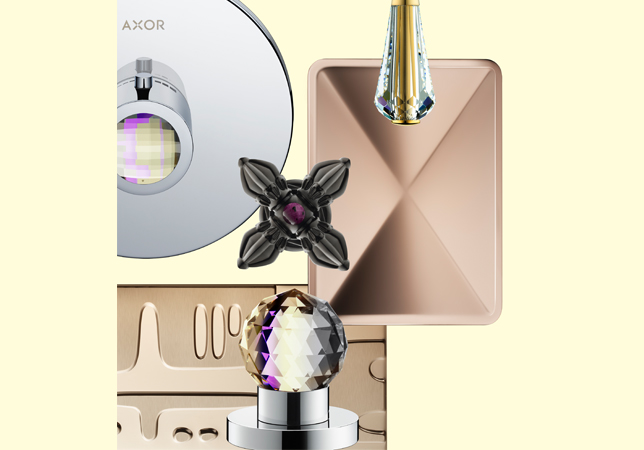

AHEC has used thermally-modified timber (now known generically as TMT) to showcase its potential for outdoor application in a number of its design collaborations. The first project was the Infinity Bench designed by Martino Gamper for the 2012 London Design Festival. In his unique design, Gamper used five different thermally-modified American hardwood species: tulipwood, ash, soft maple, red oak and yellow birch. The range of species used allowed for an exciting contrast in colours, grains and textures. Other bench design collaborations in thermally-modified American hardwoods include Emirati designer Khalid Shafar’s CITY’s Bench in Dubai and Australian Ben Percy’s design for Sydney Indesign 2013. An interesting project also using TMT was ‘The Cocoon’, a collaborative installation between T.ZED Architects and AHEC, which was initially designed for Downtown Design Dubai 2016 and is now serving as an observation deck at the Dubai Creek Harbour Promenade.

Building with wood

In construction, there is no other material that comes anywhere near wood in its potential to offer environmental benefits. Recent developments in construction timber products such as cross-laminated timber (CLT) and glued-laminated (glulam) beams have meant that structural design in timber for buildings has been raised to another level. There are significant advantages to building in wood too; including lower foundation costs, as timber structures are invariably lighter; and an overall shorter construction time. Back in 2000, Hopkins Architects used American white oak for the Arup-designed grid-shell roof structure over the courtyard of Portcullis House in Westminster. Initial strength testing showed American white oak to have a strength class of D50, roughly twice the strength of high-grade softwood. This meant that more slender timber members could be used, allowing for structural performance along with aesthetic design.

The use of white oak in Portcullis House prompted AHEC to test four commercially-important species for their strength values, so that these could be incorporated into the Eurocodes and design standards. White oak, red oak, ash and tulipwood were tested to EN338. This standard defines a range of strength classes based on values for bending strength, stiffness and density. All of these values were published in AHEC’s technical guide Structural Design in American Hardwoods, which is available on the AHEC website (www.americanhardwood.org). Interestingly, American tulipwood, although meeting the D40 strength and stiffness requirements, did not have the necessary density in order to permit it to be classified.

More recently, an engineering marvel made of American white oak features in the redevelopment of the Warner Stand at one of the world’s most iconic sporting facilities, Lord’s Cricket Ground in St John’s Wood, London. In this pioneering project, the roof of the stand is formed from 11 cantilevered glulam American white oak beams, manufactured in Germany by specialist timber fabricators Hess Timber, that radiate dramatically from the corner of the ground, paving the way for brave new structural uses of sustainable American hardwoods. Each beam measures 900 mm by 350 mm at the deepest point. The longest glulam beam weighs approximately 4 tonnes and measures 23.4 m in length, the same as 26 cricket bats lined up nose to tail. The new structure is more than an aesthetic success and crowd pleaser. It’s the first time the species has been employed in this format on this scale and in such a performance-critical environment – forming the primary structure of a roof projecting out over 2,674 spectators.

AHEC’s long-standing partnership with the London Design Festival has enabled it to showcase a number of ground-breaking structural collaborations using American hardwoods in iconic London locations. The first of these was in 2008, with David Adjaye’s Sclera pavilion, which used laminated and engineered American tulipwood. Perhaps even more intricate was the 12.5-m-high American red oak Timber Wave, erected outside the entrance to the Victoria & Albert Museum in 2011. Designed by Amanda Levete of AL_A with Arup, this pushed structural design in timber to its very limits. Here, curved chords made from 7-mm lamellas were glued together to form wavy laminated beams and the whole was held together with a series of cross-ties.

CLT is quickly becoming established as an important construction material. Made from low-cost softwood, it is essentially a thicker version of plywood that is ideal for making structural wall panels and floor cassettes. So, the next structural collaborative project for AHEC at the London Design Festival set out to show that American hardwoods could also be considered as the raw material for structural CLT. The result was the innovative Endless Stair, designed by Alex de Rijke of dRMM. This complex, free-standing structure explored the first use of hardwood CLT, using American tulipwood in this Escher-inspired series of staircases. While in situ, the Endless Stair allowed for many fine views over London and the Thames from its location outside the Tate Modern Gallery.

Building on its experience with the Endless Stair, dRMM designed the world’s first building made from hardwood CLT in the UK. Supported by AHEC, the opening of Maggie’s Oldham was a pivotal moment for modern architecture and construction.

dRMM chose tulipwood for the design of Maggie’s Oldham for the positive influence wood has on people and for the beauty, strength and warmth inherent to American tulipwood. All in all, the project has been constructed from more than 20 panels of five-layer cross-laminated American tulipwood, ranging in size from 0.5 m to 12 m long, which were developed by CLT specialists – Züblin Timber.

For AHEC, Maggie’s Oldham is one of the most important developments in a decade of research and development into structural timber innovation and one that could broaden the use of CLT in the construction industry. The creation of this product and significant use of hardwood will hopefully transform the way architects and engineers approach timber construction.

Tulipwood is particularly useful in structural applications given its very high strength-to-weight ratio. In fact, American tulipwood CLT is around three times stronger and stiffer in ‘rolling shear’ than its softwood equivalent and its potential in wood construction is extremely promising. Through AHEC’s vision, sustainable American hardwoods are now beginning to enter new and exciting commercial markets. As the world re-embraces timber as a building material, it is hoped that they will become recognised more for the possibilities they can offer in all aspects of design and construction.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)