UNM researchers are working on refining their officially patented bendable concrete material design.

UNM researchers are working on refining their officially patented bendable concrete material design.

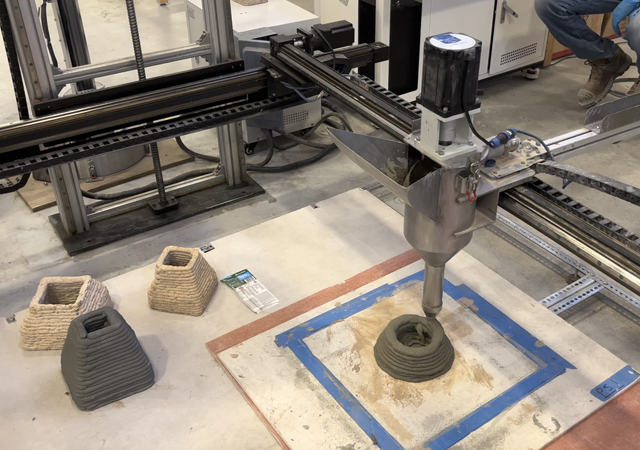

Armed with a 3D concrete printer, careful measuring tools, and just the right ingredients, a team at The University of New Mexico in the US has designed what is described as “the construction building blocks of the future” – bendable concrete material, the design of which is officially patented.

Traditional construction relies on people operating heavy machinery to place steel or wood beams to create a building frame, but the process can be dangerous and expensive. It’s just one of the material and manufacturing problems Maryam Hojati, assistant professor in the university’s Gerald May Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering, hopes to solve.

Another problem is infrastructure maintenance, which is necessary because of the brittle nature of concrete which suffers cracks. Even concrete reinforced with steel requires ongoing repair, which means regular maintenance on everything from buildings and bridges to sidewalks. A more resilient material could make public infrastructure longer-lasting and less expensive to maintain.

“Concrete by itself does not show any tensile properties, meaning if you have a piece of concrete and start pulling it apart, it can easily break. It’s a very brittle material,” Hojati said.

|

|

Hojati and Zafar discuss the results of their tests. |

Concrete’s tendency to fracture under stress is especially problematic when it comes to natural disasters and weather events like earthquakes and winds that put lateral stress, or tension, on buildings.

“The material should hold and resist both tension and compression. Concrete is a great material for compression, but when it comes to tension, it’s a weak material,” she said.

Researchers worldwide have explored what materials and processes might solve these problems. Some structures have been built in part with 3D printers, but so far, most processes rely on the placement of key materials like beams or rebars, limiting the automation that 3D printing should offer. To print something without those supports, the material must be strong enough to hold itself up without getting stuck in the printer.

Muhammad Saeed Zafar, who received his PhD in summer 2024 and worked as a graduate research assistant for Hojati, created a substance that might fit the bill.

“If we talk about 3D printing or additive manufacturing in the field of metals and plastics, it’s at a very advanced stage, but concrete printing is still developing,” Zafar said. “If we can successfully design ultrahigh-ductile material without using conventional steel bars, it will solve the problem of the incompatibility of reinforcement with the 3D printing process.”

The resulting substance, known as self-reinforced ultra-ductile cementitious material, was patented last August by UNM Rainforest Innovations on behalf of Hojati, Zafar and Amir Bakhshi – master’s degree student – who worked on the project as a research assistant and early in its development. Zafar published his research on substances in construction and building materials last year.

“The basic purpose of doing this work was to address the problem of reinforcement in 3D concrete printing,” Zafar said. “We claim that 3D concrete printing is an automated process.” But the conventional reinforcing methods are compromising the automation in this process.

The ultra-ductile cementitious material must contain enough fibre to stand firmly on its own while maintaining a viscosity that allows it to pass through the printing nozzle without getting stuck.

While it might sound simple, finding the right balance is a complex research challenge: too little fibre in the mix and the printed shapes might cave in on themselves; too much fibre and the material won’t make it very far in the printing process. To test the viability of the materials, they must be precisely mixed, measured and printed.

Even after designs are printed in several different shapes and designs, including small structures, prisms and dog bones, they must be tested for their bending and direct tensile strength. The researchers repeated this process and explored mixes made of many materials and fibre, like polyvinyl alcohol, fly ash, silica fume and ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene fibres.

The resulting patent offers four different mixes with up to 11.9 per cent higher strain capacity.

“Because of the incorporation of large quantities of short polymeric fibres in this material, it could hold all of the concrete together when subjected to any bending or tension load,” Hojati said. “If we use this material at a larger scale, we can minimise the requirement of external reinforcement to the printed concrete structure.”

The development of a bendable, printable concrete-like substance was funded by grants from the Transportation Consortium of South-Central States (Tran-SET), Region Six’s University Transportation Center. The grants funded three research projects: developing a 3D printable engineered cementitious material, evaluating the material’s properties in both fresh and hardened states, and developing a 3D printable eco-concrete.

After the first two project phases and many designs, researchers successfully designed the material the team submitted for a patent.

Eventually, 3D concrete printing technology could help astronauts explore other planets. The constraints of space travel make traditional construction unlikely, if not outright impossible. Heavy materials like steel beams and the large workforces required to place them are too difficult to transport. NASA and other space agencies are looking for alternative construction methods with hopes that bots equipped with 3D printers may one day be able to solve the problem. Hojati is involved in several projects that address space construction challenges.

Here on Earth, new materials like the one developed at UNM could eventually offer benefits like greater resilience to natural disasters, less frequent maintenance, and more automation in the construction process.

“This was very successful research. This material has 3D printing property and very high structural viability that could be used in the construction industry,” Hojati said.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)