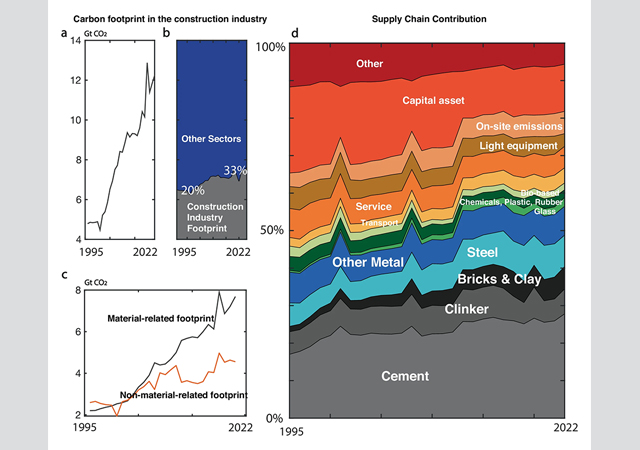

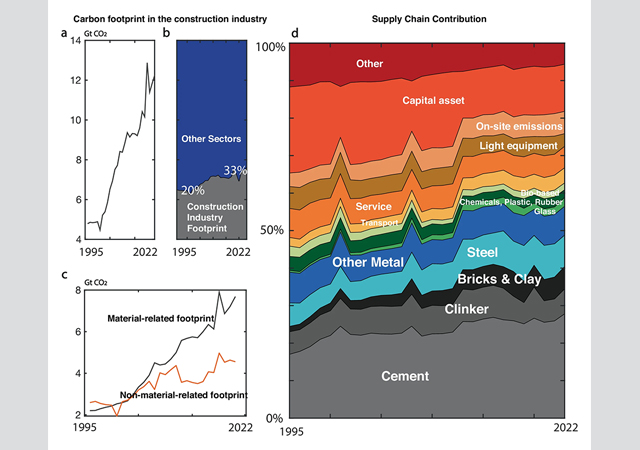

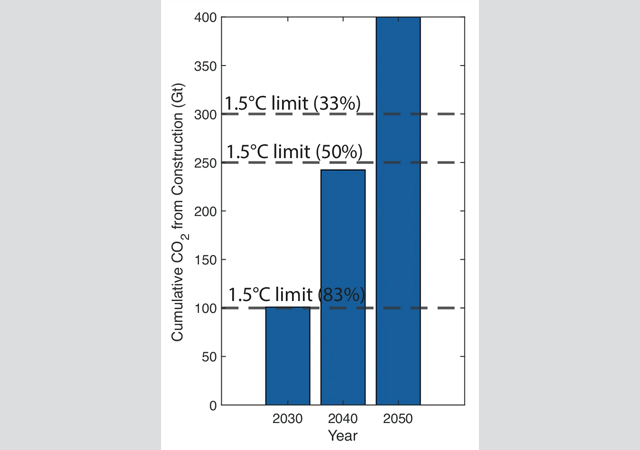

A recent Nature Communications study indicates that even if all other sectors went net-zero today, emissions from construction alone would still push the world beyond the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 deg C target by 2050. The sector produces roughly a third of global CO₂ emissions, mostly from manufacturing cement, steel, and bricks.

The authors call for a global “material revolution” suggesting a shift to bio-based, circular, and reused materials. Their analysis found that of the 12.2 Gt CO₂ emitted in 2022, cement, clinker, bricks, and clay made up 40 per cent of the total, with metals adding another 15 per cent. These materials together have become more carbon-intensive over time – their combined share of construction emissions has risen from 39 per cent in 1995 to 57 per cent.

While the paper recommends replacing concrete and steel with bio-based materials, experts from Exergio, a company that develops AI-based tools for energy efficiency in commercial buildings, caution that the problem doesn’t stop at the construction site – even buildings made from carbon-neutral materials keep wasting energy after they start operating.

|

|

Cumulative CO2 emissions from the construction industry by 2030, 2040, and 2050, compared with the 1.5 °C Paris Agreement goal at 33 per cent, 50 per cent, and 83 per cent probability levels. |

“When buildings become operational, energy waste happens quietly: we see that heating and cooling systems start working against each other, sensors give inaccurate readings, and rooms stay heated or cooled long after people leave. Those losses add up fast,” explains Donatas Karčiauskas, CEO of Exergio. “The same inefficiency that starts in material production continues in operation. It just changes form.”

Karčiauskas says the focus on carbon-neutral materials overlooks what’s right in front of us.

“Switching the world’s building stock to new materials will take decades and cost trillions – and even then, buildings would still waste 40 per cent of global energy,” he says. “We already have a faster fix. Optimising how systems run can cut up to 30 per cent of that waste now, without rebuilding anything.”

That’s the approach Exergio has used in its own projects.

Its AI-based platform links to existing building management systems and continually adjusts heating, cooling, and ventilation. By analysing live data such as occupancy, outdoor weather, and temperature shifts, it corrects setpoints automatically before waste builds up.

“Our approach is a soft, or a digital, retrofit,” Karčiauskas adds. “We don’t replace equipment, but make it think. For example, the system keeps air at comfort levels where people actually are and trims what’s not needed elsewhere.”

While the Nature Communications study centres on material emissions, Exergio points out that the same logic applies to deep renovations, which are often suggested as another alternative to reduce emissions in buildings.

Replacing façades, windows, or HVAC equipment at scale demands carbon-intensive materials the study links to rising emissions. Such upgrades may improve efficiency in the long run but add new emissions today, Karčiauskas says.

He warns this risks repeating the same cycle under a different name.

“Both embodied and operational emissions are growing,” adds Karčiauskas. “We see the highest potential for cutting waste not in new projects but in existing buildings, especially across Asia, where demand and energy intensity are soaring. Optimising those systems could cut emissions immediately, without producing another wave of materials.”

The study claims that Asia now produces over 70 per cent of construction-related CO₂. China emits about six gigatons, India just over one – together, more than the rest of the world combined.

North America and Europe build less but still rely on concrete and steel. Africa and the Middle East, meanwhile, expand faster each year as cities grow. The study concludes that emerging regions must use fewer materials, while developed ones need to make existing buildings run smarter.

“Europe doesn’t need more concrete, but smarter energy management systems. Asia needs to stop locking in waste from day one. Both sides can act now, no new tech required. If policymakers ignore operational waste, they risk repeating the same blind spot until 2050. Renovations and material swaps remain essential, but AI-enabled building management can reduce waste immediately, and with minimal cost,” Karčiauskas adds.

.jpg)