Jordan … make good choices in selection of experts.

Jordan … make good choices in selection of experts.

A recent case has reminded us of the need to respect the particular status of expert witnesses and their evidence. As we have observed before, expert witnesses have an overriding duty to assist the court (or arbitral tribunal) impartially on matters within their field of expertise, and not to act as an advocate for their instructing party.

We have looked before at “expert shopping” and the consequences of a party going beyond legitimate grounds for replacing an expert witness. Today, we are covering some of the same ground but also considering the wider dangers of undue involvement by lawyers in the procurement and presentation of expert evidence; including interference by lawyers in the drafting and editing of an expert witness’s report.

This case, unusually, is about a domestic construction project, but the principles apply generally. The claimants (Mr and Mrs Glover), the owners of a house, engaged several parties to design and carry out renovation works on it including creating a new basement. Those parties included a structural engineer. Unfortunately, the works caused damage to an adjoining property and to other properties, for which the claimants, of course, were liable. So, the claimants sought recovery of their losses from several of their project team including the contractors and the structural engineers.

In support of their action, the claimants instructed a Mr Hardy as their expert witness in structural engineering and, as is usual, Mr Hardy contributed to an Experts’ Joint Statement. This is a document which is developed between the parties’ appointed experts, in order to identify resolved and unresolved issues; and to frame those unresolved issues in such a way as to assist the court (or arbitral tribunal) in making a decision on them.

In the usual way, this Experts’ Joint Statement went through several iterations as it was developed. However, the experts for the sixth defendant (AXA XL Insurance Co) noticed significant changes in Mr Hardy’s statements between Versions 3 and 4, such that they suspected interference from the claimants’ lawyers, in breach of the (English) Civil Procedure Rules and the Technology and Construction Court Guide, which deals with Experts’ Joint Statements at s.13.6 and states, at s.13.6.3:

“Whilst the parties’ legal advisers may assist in identifying issues which the statement should address, those legal advisers must not be involved in either negotiating or drafting the experts’ joint statement. Legal advisers should only invite the experts to consider amending any draft joint statement in exceptional circumstances where there are serious concerns that the court may misunderstand or be misled by the terms of that joint statement. Any such concerns should be raised with all experts involved in the joint statement.”

As we can see, the scope for (legitimate) involvement by lawyers in an Experts’ Joint Statement is essentially limited to remedial intervention to assist the understanding of the Statement – and it needs to be done openly, involving all appointed experts.

The sixth defendant’s lawyers wrote to the claimants’ lawyers asking directly whether there had been any influence exerted by them, such as redrafting Mr Hardy’s existing statements to add new opinions or altering existing opinions. There followed inconclusive correspondence and the sixth defendant’s lawyers eventually applied for an order prohibiting the claimants from relying on the evidence of Mr Hardy.

At this point, the claimant’s lawyers conceded that they had made extensive changes to the Statement. The claimants made their own application to replace Mr Hardy as their expert on structural engineering; and as part of that application, they disclosed the correspondence in which the changes were made. They explained that their objective was to make the Statement reflect the pleaded issues. They submitted that they had taken this to be a legitimate purpose and that their action was not an intentional disregard of the rules. They apologised to the court. The court accepted the claimants’ lawyers’ actions as genuine, if misguided, and accepted their apology.

Then, addressing the claimants’ application to replace their expert witness, the court took a pragmatic line. This involved balancing the claimants’ need to bring credible expert evidence in order to litigate the dispute effectively, against the consequences for the defendants arising from the procedural wrongdoing, including delays and additional cost. Crucially, the court concluded that a change could be allowed without delaying scheduled trial dates and, in furtherance of the overriding objective to deal with matters at proportionate cost, the court allowed the claimants’ application.

There was, however, a price for the claimants to pay, including the sixth defendant’s costs of both applications and 30 per cent of the sixth defendant’s costs in dealing with the original Experts’ Joint Statement and the new expert’s opinion – all to be assessed on an indemnity basis.

This is in line with the approach we looked at previously, in which a party applied to replace an expert in which they had lost confidence. The scope to allow such an application is limited and, if granted, the applicant can expect to pay all costs and give full disclosure of dealings with the original expert. So, the lessons are the same: make good choices in selection of experts and keep to the rules.

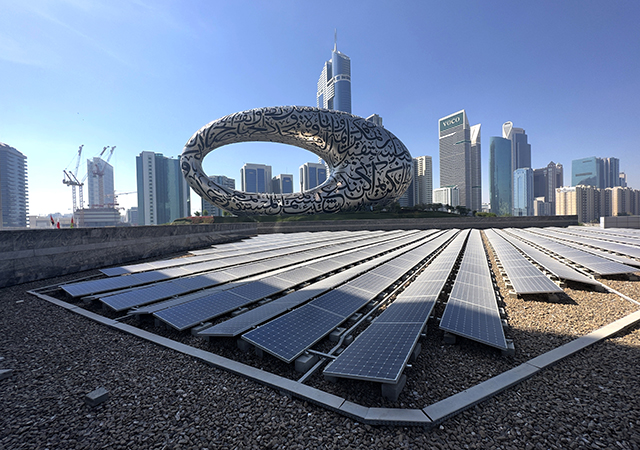

* Stuart Jordan is a partner in the Global Projects group of Baker Botts, a leading international law firm. He has relocated to the group’s Dubai office this month, to better develop its construction offering in the Gulf. Jordan’s practice focuses on the oil, gas, power, transport, petrochemical, nuclear and construction industries.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)